Yes, they aren’t! Agenda 2063, which has recently been cast in AU Stone, envisions a prosperous continent built on a solid foundation of universal energy. The widely shared expectation is that electricity for all will catalyse economic transformations of the sort that lift millions out of poverty. Millions, not a few thousand elites.

We need to mobilize approximately $91 billion by 2030 to deploy 160,000 mini-grids in sub-Saharan Africa to achieve this goal. Yet the challenge is as much about financing as it is about analytical acumen and actionable results. Perhaps more so. How do we find the right sites, design successful business models, navigate complex regulations, and create community adoption of core technologies? Think 4th Industrial Revolution. Increasingly, the answer lies in artificial intelligence (AI) and other digital tools.

AI-backed planning systems can accelerate project preparation, mitigate investment risks, and optimize resource allocation in ways that conventional methods have not, and, to be brutally frank, cannot. By analyzing satellite imagery, demographic information, and economic indicators together, these systems can pinpoint a suitable electrified site in days, not months. Using advanced modeling techniques, AI-powered decision-support tools can help determine the effective tariff structure after considering different policy scenarios, identify and nip equipment failures in the bud before they occur, and much more. Development finance institutions and private investors have these capabilities, and this means that they can perceive a lower risk than before. This has already resulted in a reduction in capital costs. If this continues, it could definitely save billions in investment costs.

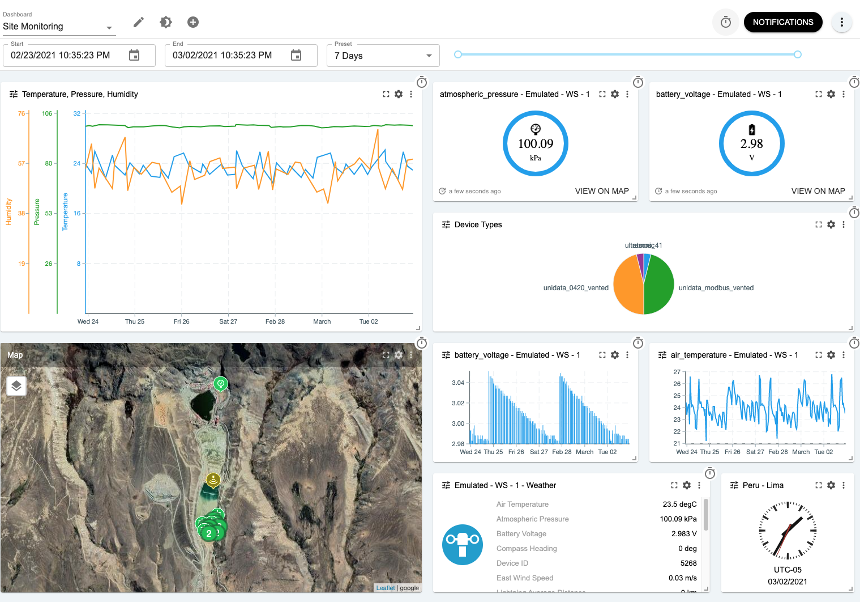

Furthermore, tools powered by AI and capable of generating transparency will help improve governance and regulatory compliance when:

- The performance data of every mini-grid comes to centralized dashboards.

- Automated regulatory reporting becomes a boring reality.

- Project developers can prove real-time compliance.

- The entire energy sector becomes a lot more bankable.

We need humans and an intelligent agent infrastructure to help mobilize the private capital that will complement public funding from domestic and international sources (both public and private). Stop thinking about this as a nice-to-have addition to traditional approaches.

The all-important question is whether the digital tools currently used in Africa’s mini-grid sector can do the job. A recent analysis finds that: (1) some tools are mature and deployed, but (2) critical capabilities are either absent or stuck in the lab. Refer to the table below for a brief overview of the current state of affairs.

The Current State: Successes, Major Gaps

Researching digital tools used on African mini-grids shows there are differences in maturity and operational readiness.

Table 1: Summary of Deployment Status

| Tool/Method | Status | Geographic Deployment | Addressing Obstacles |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIDA | ✅ Operational | West Africa, East Africa | Site selection, demand forecasting |

| HOMER Software | ✅ Widely Deployed | Global (190+ countries) | Financial modeling, optimization |

| LEAP | ⚠️ National Planning | 13+ African countries | National energy planning, policy analysis |

| enee.io | ✅ Operational | Nigeria, expanding | Predictive maintenance, monitoring |

| Odyssey Platform | ✅ Operational | Nigeria | Financing, regulatory compliance |

| MicroGridsPy | ⚠️ Research/Pilot | Limited academic use | Optimization modeling |

| Digital Twins | ⚠️ Pilot Stage | Research labs | System optimization |

| AI Predictive Maintenance | ⚠️ Emerging | Growing in industry | Equipment reliability |

| Policy Simulation Tools | ❌ Not Deployed | N/A | Policy analysis |

| Agent-Based Modeling | ❌ Not Deployed | N/A | Growing in the industry |

The good news? Tools like VIDA (Village Data Analytics) and HOMER have already shown their value in deployment: VIDA accurately predicted high-revenue villages across Tanzania and West Africa, while HOMER has more than 250,000 designers in over 190 countries using it. Nigeria’s enee.io recently raised $250,000 in funding to grow its IoT-based monitoring systems business. We have evidence. We’re moving!

The not-so-happy news? Two significant capability gaps are entirely missing: (10 mini-grid-specific policy simulation tools and (2) agent-based models to aid community adoption. I came here to tell you, these are not “just small, small abstract things” that are missing; they are aspects of the major challenges that mini-grids face when trying to scale from pilots to programs.

The Promise and Limits of AI Enhancements.

Digital tools are evolving rapidly due to recent innovations. LEAP (Long-range Energy Alternatives Planning System) is an energy modeling software that is widely used for national energy planning across 13 African countries, including Ghana, Nigeria, and Ethiopia. Recently, LEAP launched an energy modeling assistant based on generative AI. This tool utilizes GPT to enable users to interact with the LEAP system’s well-oiled features using natural language, generate automation code, and significantly reduce the technical barrier to sophisticated energy modeling.

Similarly, enee.io and the like are integrating “State of Health” features to their platform with help from AI, which predicts battery failure before it happens. Let that sink in: before it happens! Odyssey continues to digitize and streamline the mini-grid financing workflow. These features make things easier to use, speed things up, and prevent things from going thump in the middle of the night.

With replicability and scale in mind, let’s always be honest about the impact these improvements can have, as well as what they can’t.

What They Do and Do NOT Do

Table 2: What AI Assistants DO vs. Do NOT Do

| What AI Assistants DO | What They Do NOT Do |

|---|---|

| Make existing tools easier to use | Add agent-based modeling capabilities |

| Speed up workflow through automation | Enable community behavior simulation |

| Reduce learning curve | Reduce the learning curve |

| Assist with code generation | Add mini-grid-specific deployment features |

| Improve accessibility | Transform planning tools into operational systems |

Consider the comparison in Table 3

Table 3: Tool Category Comparison

| Tool Category | Purpose | Scale | Current Status in Africa |

|---|---|---|---|

| LEAP (with AI assistant) | National energy policy planning | Country/regional | ✅ Deployed for this purpose |

| Policy Simulation Tools | Advanced mini-grid policy scenario modeling | Mini-grid sector specific | ❌ Not deployed |

| Agent-Based Modeling | Simulate household/community adoption behavior | Village/community level | ❌ Not deployed |

What Africa Actually Needs.

Africa requires capabilities unique to its mini-grid deployment challenges. To truly leverage the full potential of minigrids to drive energy transitions, we need capabilities that currently don’t exist anywhere.

For Mini-Grid-Specific Policy Simulations:

– Project-level modeling of tariff structures.

– Grid-arrival scenario analysis.

– Simulate business models of developers under different regulations.

– Subsidy optimization algorithms.

– Regulatory compliance scenario testing.

For Community Behavioral Modeling:

– Individual household adoption dynamics.

– Effects of social networks within villages

– Cultural factor integration.

– Technology diffusion patterns.

– Local Economic Context Influencing Willingness-to-Pay Modeling

Why can’t existing tools simply be adapted? You may ask. It’s because the challenges are fundamentally different. An energy model at the national level, which operates at the GDP and sector levels, cannot capture the village elder’s role in technology adoption or the impact of seasonal agricultural income on payment patterns. Similarly, it overlooks the cultural dynamics that determine whether women can make decisions about household energy purchasing. I distinctly remember a certain woman who attended an introductory workshop under the AREED project back in the day, only to be replaced by someone who insisted he should be the real beneficiary of the enterprise development course.

No one-size-fits-all model for urban solar has proven successful to date. So, for instance, solar plans developed for Texas or Germany – even using the most sophisticated agent-based models – cannot be simply transferred to rural Tanzania. The social and economic conditions are just too different from a whole-systems perspective. So are things like access to energy, the level of the community in the settlement system hierarchy, and the decision-making processes.

Building Africa’s Digital Energy Toolkit

I am not saying these tools (e.g. LEAP or HOMER or VIDA etc ) do not add value. Instead, it is a call for Africa to develop complementary capacities that serve its needs. Several pathways forward emerge.

To kick things off, we should focus on investing in Africa-based research and development. Targeted investment should go to universities and research institutions across the continent to build mini-grid policy simulation platforms, which would be calibrated to African regulatory environments and behaviour models based on African data.

Next, we create open source frameworks, like MicroGridsPy, to build tools that the entire African energy community can use, modify, and adapt. This ensures that tools are accessible to all and maintain a local response, rather than requiring an expensive license.

We must also build quality data infrastructures for agent-based models and policy simulators. It goes without saying that these require a concerted effort to gather, harmonize and share anonymized data on mini-grids, customer behaviour and policy impacts.

Finally(?) we need to bring energy developers, data specialists, anthropologists, economists, and community organisers. All participants must get access to tools that can help us know what works and what doesn’t on mini-grids.

The Stakes Are Too High for Half-Measures

Yes, they certainly are! Around 600 million Africans do not have access to electricity, and with only 7 years remaining until the SDG 2030, there is no time for second best. When a mini-grid project fails, when a tariff structure is miscalculated, or when a community rejects an ill-designed system, the consequence is every wasted resource package and every delayed development package.

Digital technologies, along with Artificial Intelligence, promise immense potential for accelerating Africa’s energy transition and securing the necessary finance. For Africa to realize this promise, it must build specific analytical capabilities, rather than simply adapt tools designed for fundamentally different contexts.

Africa must ponder whether it can invest in building its own digital energy tools. The question is whether it can afford not to.