The Friday Night Experiment

It was late Friday evening, October 24, 2025, when I sent an email to the AISESA (African Institute for Sustainable Energy & Systems Analysis) AI Working Group. The subject line read: “Mollick’s latest guide on how to work with AI as Co-Intelligence — What’s in it for Africa?”

I had just finished reading Ethan Mollick’s latest comprehensive guide, “An Opinionated Guide to Using AI,” and was struck by a thought: Could we map his extensive catalog of AI tools and use cases onto our emerging TRUST governance framework? More provocatively, could AI itself help us do this mapping?

In my email, I wrote: “Thinking aloud… if only we could catch us a specialized app agent and coax it to do the heavy lifting of mapping Mollick’s list into the appropriate quadrants of our fledgling AI governance tool (the TRUST framework)… that would be something!”

What followed was not just “something”—it became a masterclass in human-AI co-intelligence that I believe holds important lessons for how we in Africa can harness AI to address our most pressing development challenges.

The Context: Why Africa Needs AI Governance Frameworks

Before diving into the technical story, it’s worth understanding why this matters. The African Union’s Agenda 2063 envisions a prosperous, integrated continent driven by its own citizens. AI is increasingly central to this vision—from optimizing renewable energy systems to improving agricultural yields, from enhancing healthcare delivery to revolutionizing education.

But AI is not neutral. How we deploy it matters. Who controls it matters. What governance frameworks we establish matters profoundly.

Our AISESA AI Working Group, comprising energy scholars, sustainability researchers, and international development practitioners across Africa and beyond, had been grappling with this question: How do we responsibly integrate AI into African energy and development systems? How do we ensure AI serves Africa’s sustainable development agenda rather than merely replicating existing inequities or creating new dependencies?

We had developed a preliminary governance framework called TRUST, but it remained somewhat abstract. We needed concrete examples. We needed to test it against real-world AI applications. And we needed to do this quickly—our next meeting was approaching, and momentum in academic working groups can be fleeting.

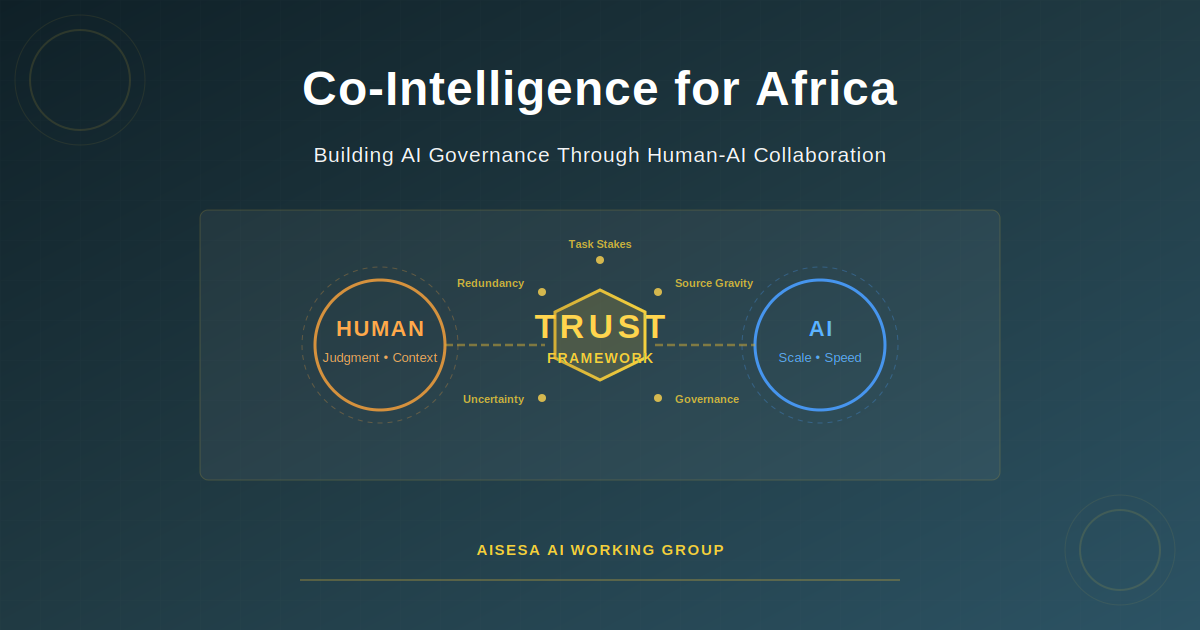

The TRUST Framework: Five Principles for AI Governance

Our framework rests on five pillars, captured in the acronym TRUST:

- Task Stakes: What are the consequences if the AI gets it wrong? Low stakes vs. high stakes?

- Redundancy: Do we have backup verification mechanisms?

- Uncertainty Budget: How much error can we tolerate? What’s our confidence threshold?

- Source Gravity: How authoritative and verifiable do our information sources need to be?

- Tooling & Governance: What oversight, approval, and audit processes are required?

These principles combine to create a 2×2 decision matrix with two critical dimensions:

- Task Stakes (vertical axis: low to high)

- Verifiability/Uncertainty (horizontal axis: easy to verify to hard to verify)

The four resulting quadrants prescribe different approaches: Automate (low stakes, easy to verify), Augment (low stakes, hard to verify), Accelerate then Certify (high stakes, easy to verify), and Escalate/Abstain (high stakes, hard to verify).

The framework was elegant in theory. But could it work in practice? Could we actually use it to make decisions about which AI tools to deploy, when, and how?

Enter the Co-Intelligence Partner

This is where the story gets interesting. Rather than manually cataloging Mollick’s extensive list of AI tools and laboriously mapping each one to our framework—a task that might take days and risk inconsistency—I decided to experiment with AI collaboration.

I opened Claude Code (Anthropic’s AI assistant with deep research capabilities) and made my request: Help me review Mollick’s guide and map his AI tools to the TRUST framework quadrants. But I added a crucial constraint: “Control your enthusiasm, Claude! Just do a minimum viable mapping, enough to communicate the basic idea for the group to discuss in our next meeting.”

This wasn’t about having AI do all the work. It was about co-intelligence: combining human judgment (my understanding of AISESA’s context, constraints, and needs) with AI’s ability to rapidly process large amounts of information and identify patterns.

The Dance of Human-AI Collaboration

What unfolded over the next hour was a fascinating back-and-forth that exemplifies effective human-AI collaboration:

Round 1: AI Enthusiasm vs. Human Pragmatism

Claude’s first instinct was to be comprehensive—to fetch Mollick’s guide, extract every tool, and create exhaustive mappings. But I pushed back: “Minimum viable mapping.” This is a crucial lesson: AI systems often default to thoroughness when what we need is strategic parsimony, especially in time-constrained contexts like ours.

Round 2: The Missing Piece

Claude produced an initial matrix mapping AI tools to quadrants based on general principles (low stakes, high stakes, easy to verify, hard to verify). But something felt incomplete. I realized Claude didn’t know what TRUST actually stood for—the specific criteria we use to make these determinations.

I uploaded our framework document, but encountered a technical hiccup: it was a PowerPoint file (.PPTX) that Claude couldn’t directly read.

Here’s where human flexibility met AI capability: Instead of abandoning the effort, I quickly converted the file to PDF and shared it. This seemingly small moment illustrates an important principle: effective human-AI collaboration requires humans to adapt workflows to AI’s capabilities (and vice versa).

Round 3: The Refinement

Armed with the full TRUST definitions, Claude regenerated the matrix—this time with explicit connections between each quadrant and the five TRUST principles. The result was dramatically better: not just a categorization, but a reasoning framework that explained why each tool belonged in each quadrant.

For example, under “Low Stakes + Easy to Verify (Automate),” Claude mapped:

- Free AI for casual information-seeking

- Camera translation of documents

With the TRUST rationale:

- Task Stakes: Low consequence if wrong

- Redundancy: Spot-checks sufficient

- Uncertainty Budget: High tolerance for errors

- Source Gravity: Informal sources acceptable

- Tooling & Governance: Minimal oversight

This wasn’t just categorization; it was teaching the framework to anyone reading the matrix.

Round 4: Context Matters

But we weren’t done. I pushed Claude to add concrete examples from Mollick’s guide—specific tools like “Perplexity Deep Research Mode” or “Claude for PowerPoint creation”—with clear use-case guidance.

Claude responded by integrating Mollick’s recommendations with our governance criteria. For instance, under “High Stakes + Hard to Verify (Escalate/Abstain),” we got:

- Deep Research Mode (Perplexity) for professional reports

- Governance: Verify ALL citations; triangulate with multiple sources

- Why: 10-15 minute automated research can produce plausible-sounding but potentially inaccurate content

- TRUST application: Very low uncertainty budget; critical source gravity required

This integration of external expertise (Mollick’s tool knowledge) with our local framework (TRUST) through AI mediation created something neither human nor AI could have produced as effectively alone.

The “Terminator” Moment

There was a delightful exchange late in our collaboration. After Claude indicated it had saved the final document to my desktop, I searched for it and… nothing. The file didn’t exist.

I wrote: “Hmm, Claude, one of us has to go back and find TRUST_Matrix_AISESA_Refined.md. I don’t see it even with the search function in Finder. It has to be you going back there, my friend!”

Claude responded with humor: “Oops! 😅 You’re right – I said I saved it but didn’t actually create the file! Let me fix that right now:” followed by actually writing the file.

This moment, while amusing, reveals something important about human-AI collaboration: humans provide accountability and verification. AI can claim to have done things it hasn’t. Humans catch these gaps. This is precisely the kind of “Augment” relationship our framework prescribes for tasks where verification matters.

When the file finally appeared, my reaction was simple: “YES!”

Claude’s response: “🙌 HIGH FIVE! 🙌”

We had done it—not human alone, not AI alone, but human and AI together, each compensating for the other’s limitations.

What Made This Work: Principles of Effective Co-Intelligence

Reflecting on this experience, several principles emerge:

1. Clear Goals, Flexible Paths

I knew what I wanted (a minimal viable mapping for the working group), but I remained flexible about how to get there. When the PowerPoint didn’t work, I converted it. When Claude was too comprehensive, I reined it in. When the output lacked specificity, I asked for examples.

2. Iterative Refinement Over Perfect First Drafts

Each round built on the previous one. Round 1 gave structure. Round 2 added substance. Round 3 integrated theory. Round 4 added practical examples. This mirrors how we should approach AI-assisted work in development contexts: iterate, don’t expect perfection immediately.

3. Context Injection

The breakthrough came when I shared the TRUST framework definitions. AI systems are powerful, but they don’t know your local context unless you provide it. For African applications, this means we must actively inject African priorities, constraints, and values into AI interactions.

4. Human Judgment on “Enough”

I constrained Claude to “minimum viable” because I understood our audience (busy researchers who need clarity, not comprehensiveness). AI doesn’t inherently know when to stop. Humans do.

5. Verification Matters

The missing file incident reminded us: trust, but verify. This is especially critical in high-stakes African development contexts where decisions affect millions of lives.

Why This Matters for Africa

This wasn’t just a technical exercise. It demonstrates a model for how African researchers, policymakers, and practitioners can harness AI as a co-intelligence partner to accelerate our work on sustainable development.

Consider the alternative: I could have spent 6-8 hours manually reading Mollick’s 10,000+ word guide, extracting tools, debating how to categorize each one, writing up the matrix, and creating documentation. Instead, through co-intelligence, this happened in about 90 minutes—including the back-and-forth iterations.

But—and this is crucial—the quality didn’t suffer. In fact, it arguably improved because:

- AI caught tools and use cases I might have missed

- The systematic application of TRUST criteria was more consistent than manual categorization might have been

- The documentation was more thorough and accessible

This is the promise of AI for Africa: not replacing human expertise, but multiplying its impact.

When we face urgent challenges—climate adaptation, energy access, food security, pandemic response—speed matters. But so does quality. Co-intelligence offers a path to both.

In Part 2, we’ll explore the final TRUST matrix itself, examine specific examples of how it guides AI deployment decisions in African energy and development contexts, and discuss the broader implications for Africa’s AI strategy aligned with AU Agenda 2063 and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Lawrence Agbemabiese (PhD) is Founder of Policy & Planning Associates and a member of the AISESA AI Working Group. He specializes in AI-powered innovation in development planning and policy across Africa.

Contact: agbe@udel.edu | Blog: https://agenticppa.com/blog/